terrible angels

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Monday, December 11, 2006

mcewan, pynchon, and gentian violet

Regarding the dust up over charges that Ian McEwan "plagiarized" a book that he acknowledged using as a reference for his historical novel Atonement (read summary article here):

My first thought was that this was just another pathetic example of celebrity litigation. It is a baseless charge that can still be settled for a sum in order to avoid the nuisance. The necessary companion to this bottom feeder is, of course, tabloid journalism.

It is a desperate paper that will stoop to the level of besmirching the reputation of a superb writer -- one of the best contemporary English novelists -- in order to sell papers and everyone who has had a hand in this affair should be ashamed of themselves. Sadly the capacity for shame and the profession of journalism are sometimes mutually exclusive categories.

This is the problem with the way that so much of journalism is practiced today: not everything is news and not every news story has the same truth value. Indeed, the news media has a responsibility to not report every accusation, launching it into a wider public sphere and validating the claim.

- - - - - - - -

In fact, the story behind this accusation is rather sad. It turns out that the late Lucilla Andrews (who wrote the autobiography from which he pilfered some number of details and some lovely passages it must be said) felt slighted by Ian McEwen. She felt that he didn't acknowledge the importance of her book enough. Also, he never attempted to contact her or meet her.

In the giddy world of the London literati one is too busy having one's ego buffed and polished to make time for having a cup of tea with an octogenarian writer of romantic novels -- even though her autobiography was a key resource for his award winning novel. My heart does go out to her.

It is sad that McEwan could not find it in him to share a little bit of his acclaim with her -- as a gesture of generosity if not gratitude.

But there is a difference between being a narcissist and being a plagiarist.

Furthermore, I have little sympathy towards the individuals who are behind this action. It can hardly be a coincidence that this is occurring shortly after Lucilla Andrews' death -- the point in an author's career when the various leeches start attaching themselves the author's reputation -- and more importantly -- to the estate.

Even less of a coincidence is the fact that there is a Hollywood film being made of the novel. Andrews's brother has said that he is keen to make sure that his sister be given "proper credit." Indeed. Naturally that would also include the proper payment that goes with her credit.

- - - - - - - -

This charge against McEwan also illustrates the how little understanding there is about literature and the art of writing. Everyone knows that charges of plagiarism can are the way to create a scandal for a writer, but there appears to be a general confusion about what actually constitutes plagiarism. If this incident proves anything it is that there is also tremendous ignorance about literary writing and the genre of fiction.

Perhaps because literature has so much more value in England -- and writers therefore have a much higher status -- the voices of those who review books are also more significant than their counterparts in the United States, where the entire endeavor of literature is basically culturally irrelevant. Perhaps because of this additional level of importance, the British reviewers – particularly in fiction and poetry – can demonstrate a level of viciousness – even pettiness – that is rare in American criticism. Literature in this country is so invisible it doesn't need to be eviscerated in the press.

In the manner of "not saying what they mean or meaning what they say" British reviewers often undermine their subject by simply pointing out how much smarter they are than the writer under review. This method of illustrating the failings of the writer by demonstrating his or her own cleverness is a stylistic technique that would be less appreciated in the U.S. If we even understood what was being said (often it turns on some obscure word usage or some arcane knowledge that marks one as taking a certain course of study at a specific college at Oxbridge) we would be more likely to think that the reviewer was just being a pompous ass.

- - - - - - - -

This brings me to Thomas Pynchon's letter.

And what rollicking good fun that is. Starting off with his devastating first sentence:

Given the British genius for coded utterance, this could all be about something else entirely, impossible on this side of the ocean to appreciate in any nuanced way – but assuming that it really is about who owns the right to describe using gentian violet for ringworm, for heaven’s sake, allow me a gentle suggestion.

I have been rereading that sentence every now and then just because it is such a giggle. In a way he hardly needed to go any further. (To read the entire letter click here.)

I don't think of writers in terms of nations but except in the ways that nation and language are connected. And sometimes it is nice to be reminded of what the best of American writers offer, not just to the general American reading public (all twelve of them) but to the English literary world.

There are many ways that George Bush is the shame of this nation, one being that he is the preeminent speaker of a particular American idiom that utterly decimates the English language. Notwithstanding our semiliterate president, Americans tend to feel secondary to Brits with regard to the English language. Thomas Pynchon is the example of why the American idiom prevents its ossification. Or, to put it in a more vulgar way: Pynchon takes the piss out of it, Bush just pisses on it.

- - - - - - - -

Pynchon’s comparison, further in the paragraph, of the writer to the chimpanzee that is drawn to the more “vivid and tuneful” words reminded me of Flaubert’s notion of the writer creating “tunes for bears to dance to.”

Which brings me back to my point about the way that this debate illustrates an ignorance about literature. Not just how it is written but how it is read.

It is true, as Pynchon says, that no literary writer could resist “gentian violet for ringworm."

Take a look at how it works: The trochaic foot slows the reader down as the consonant sounds of shhs to rrrrs move back and under the tongue. The words themselves (gentian violet for ringworm) as well as the internal wordplay (gent, gentle, genital, inviolate, vile, violate, violent, ring, war, worm, word) create a nexus of associations between sex and marriage and rape and violence. Voila. It becomes a trope for McEwan's Atonement.

It would have been wrong for him to have left it untouched and not re-introduced the phrase to the reader again, in a new context, enriching it further. That is an example of original, creative, literary writing. (And reading).

My first thought was that this was just another pathetic example of celebrity litigation. It is a baseless charge that can still be settled for a sum in order to avoid the nuisance. The necessary companion to this bottom feeder is, of course, tabloid journalism.

It is a desperate paper that will stoop to the level of besmirching the reputation of a superb writer -- one of the best contemporary English novelists -- in order to sell papers and everyone who has had a hand in this affair should be ashamed of themselves. Sadly the capacity for shame and the profession of journalism are sometimes mutually exclusive categories.

This is the problem with the way that so much of journalism is practiced today: not everything is news and not every news story has the same truth value. Indeed, the news media has a responsibility to not report every accusation, launching it into a wider public sphere and validating the claim.

- - - - - - - -

In fact, the story behind this accusation is rather sad. It turns out that the late Lucilla Andrews (who wrote the autobiography from which he pilfered some number of details and some lovely passages it must be said) felt slighted by Ian McEwen. She felt that he didn't acknowledge the importance of her book enough. Also, he never attempted to contact her or meet her.

In the giddy world of the London literati one is too busy having one's ego buffed and polished to make time for having a cup of tea with an octogenarian writer of romantic novels -- even though her autobiography was a key resource for his award winning novel. My heart does go out to her.

It is sad that McEwan could not find it in him to share a little bit of his acclaim with her -- as a gesture of generosity if not gratitude.

But there is a difference between being a narcissist and being a plagiarist.

Furthermore, I have little sympathy towards the individuals who are behind this action. It can hardly be a coincidence that this is occurring shortly after Lucilla Andrews' death -- the point in an author's career when the various leeches start attaching themselves the author's reputation -- and more importantly -- to the estate.

Even less of a coincidence is the fact that there is a Hollywood film being made of the novel. Andrews's brother has said that he is keen to make sure that his sister be given "proper credit." Indeed. Naturally that would also include the proper payment that goes with her credit.

- - - - - - - -

This charge against McEwan also illustrates the how little understanding there is about literature and the art of writing. Everyone knows that charges of plagiarism can are the way to create a scandal for a writer, but there appears to be a general confusion about what actually constitutes plagiarism. If this incident proves anything it is that there is also tremendous ignorance about literary writing and the genre of fiction.

Perhaps because literature has so much more value in England -- and writers therefore have a much higher status -- the voices of those who review books are also more significant than their counterparts in the United States, where the entire endeavor of literature is basically culturally irrelevant. Perhaps because of this additional level of importance, the British reviewers – particularly in fiction and poetry – can demonstrate a level of viciousness – even pettiness – that is rare in American criticism. Literature in this country is so invisible it doesn't need to be eviscerated in the press.

In the manner of "not saying what they mean or meaning what they say" British reviewers often undermine their subject by simply pointing out how much smarter they are than the writer under review. This method of illustrating the failings of the writer by demonstrating his or her own cleverness is a stylistic technique that would be less appreciated in the U.S. If we even understood what was being said (often it turns on some obscure word usage or some arcane knowledge that marks one as taking a certain course of study at a specific college at Oxbridge) we would be more likely to think that the reviewer was just being a pompous ass.

- - - - - - - -

This brings me to Thomas Pynchon's letter.

And what rollicking good fun that is. Starting off with his devastating first sentence:

Given the British genius for coded utterance, this could all be about something else entirely, impossible on this side of the ocean to appreciate in any nuanced way – but assuming that it really is about who owns the right to describe using gentian violet for ringworm, for heaven’s sake, allow me a gentle suggestion.

I have been rereading that sentence every now and then just because it is such a giggle. In a way he hardly needed to go any further. (To read the entire letter click here.)

I don't think of writers in terms of nations but except in the ways that nation and language are connected. And sometimes it is nice to be reminded of what the best of American writers offer, not just to the general American reading public (all twelve of them) but to the English literary world.

There are many ways that George Bush is the shame of this nation, one being that he is the preeminent speaker of a particular American idiom that utterly decimates the English language. Notwithstanding our semiliterate president, Americans tend to feel secondary to Brits with regard to the English language. Thomas Pynchon is the example of why the American idiom prevents its ossification. Or, to put it in a more vulgar way: Pynchon takes the piss out of it, Bush just pisses on it.

- - - - - - - -

Pynchon’s comparison, further in the paragraph, of the writer to the chimpanzee that is drawn to the more “vivid and tuneful” words reminded me of Flaubert’s notion of the writer creating “tunes for bears to dance to.”

Which brings me back to my point about the way that this debate illustrates an ignorance about literature. Not just how it is written but how it is read.

It is true, as Pynchon says, that no literary writer could resist “gentian violet for ringworm."

Take a look at how it works: The trochaic foot slows the reader down as the consonant sounds of shhs to rrrrs move back and under the tongue. The words themselves (gentian violet for ringworm) as well as the internal wordplay (gent, gentle, genital, inviolate, vile, violate, violent, ring, war, worm, word) create a nexus of associations between sex and marriage and rape and violence. Voila. It becomes a trope for McEwan's Atonement.

It would have been wrong for him to have left it untouched and not re-introduced the phrase to the reader again, in a new context, enriching it further. That is an example of original, creative, literary writing. (And reading).

Thursday, December 07, 2006

pomegranates & persephone

Pomegranates are associated with the winter because of the story of Persephone. This is the myth that explains the change of the seasons and hence the passing of time and the concepts of repetition, return and of memory and loss. And sex, naturally. It is not surprising when you look at the fruit that there is a myth in which eating a pomegranate is a metaphor for sexual experience. Indeed, because Persephone eats the seeds of a pomegranate while she is in the underworld she is not allowed to leave. The story continues from there but you can find out what happens for yourself.

There are a number of places on the web where you can read the various versions of the myth. Quick little summaries are nice but keep in mind that the story is far from simple. The original version of the story is a complex poetic work written in Homeric Greek. While the changing of the seasons seems like a basic literary trope, there is little about story that is obvious in its meaning.

The Rape of Persephone -- Homeric Hymn version with links to other translations.

Encyclopaedia Mythica Version -- A shorter summary

Sunday, December 03, 2006

gifts for terrible angels

A bit of literary irony from Rilke's Duino Elegies: a melancholy angel is the perfect gift for poets, buzzkills and drama queens. Fans of Coco Rosie will get the joke. The wry gothic sensibility will appeal to Tim Burton and/or Edward Gorey afficianados. Great for that sullen teenager on everybody's holiday shopping list. Men's and women's designs. In black. Of course.

Labels:

coco rosie,

duino elegies,

poetry,

rilke,

terrible angels

Thursday, September 14, 2006

the french department

"I'm French! Why do you think I have this outrrrhageous accent?"

"I'm French! Why do you think I have this outrrrhageous accent?"kih presents:

pretend to speak french

a list of resources for those who want to mock the french language but can't be bothered to actually learn it.

- fetchez la vache - start with this essential text

- a list of french phrases - would wikipedia lead you astray?

- some useful french phrases & pronunciation tips - provides a special section for commenting on fashion

- alternative french dictionary - advanced: for those who want to make the move from irritating to obnoxious

- babelfish online translator - what could go wrong?

- learn french - free online resources

- superfrenchie's blog - cheese-eating surrender monkey sightings and the status of french fries

- comme ci, comme ça.

- comme ci, comme ça.- chacun a son goût.

- je m'ennuie.

- moi aussi.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

who in hell is kora in hell?

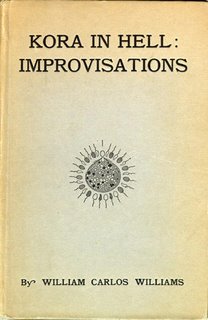

1. the book

My blog's name, Kora in Hell, has a number of allusions but the most prominant one is a book by the American poet William Carlos Williams.

Kora in Hell was written in 1918 and published in 1920. It is a unique text written in a form that defies categorization. Subtitled "Improvisations" the closest way to describing the text in familiar genre terms is as a prose poem. Specifically it is a series of paragraph entries comprised of two types of writings: (1) spontaneous writings that he composed over the course of a year -- a kind of poetic diary; and (2) italicized critical commentaries on the "diary" passages. The fragmentary form is an attempt to demonstrate the process of the imagination as it moves "from one thing to another." In doing so Williams is tracing the discovery -- and the movement towards understanding -- that the opposite of a perception can also true. In this way Kora in Hell juxtaposes the tension between -- and interdependence of -- the imagination and the objective facts--the hard objects--of the world.

The "Prologue" to Kora in Hell is considered one of the most significant statements on modern poetic form. At the time Williams was interested in Dada and the ideas of the artist Marcel Duchamp. Kora in Hell was written at the peak of this intense and significant but short-lived avant-garde movement and it is the most fully realized work of Dada poetics. It bears the hallmarks of the movement's in its absurdity, irony, chance, and the need to create art that challenges conventional ideas about art itself. It is profoundly unsentimental and scoffs at exalted conceptions of art: As befitting a work that evokes the myth of Kora's descent into hell (Kora is a figure for Percephone -- although Williams also connects the theme to Euridice), the work is often deeply pessimistic and despairing about the human condition. It is important to note that the book (and the Dada movement) were created during the time of World War I.

As befitting a work that evokes the myth of Kora's descent into hell (Kora is a figure for Percephone -- although Williams also connects the theme to Euridice), the work is often deeply pessimistic and despairing about the human condition. It is important to note that the book (and the Dada movement) were created during the time of World War I.

In keeping with the Percephone myth rebirth is a recurring motif in the work, as is the theme of returning: the flip side of the coin of renewal. This is the necessary journey of the artist who must create a break from the past in order to see the world anew. Indeed, Kora in Hell marks a major transition in Williams as a modern poet.

There is so much more to say about this book but for now let this stand as a brief "advertisement" for you to go read it for yourself.

To cite this passage please contact me here.

My blog's name, Kora in Hell, has a number of allusions but the most prominant one is a book by the American poet William Carlos Williams.

Kora in Hell was written in 1918 and published in 1920. It is a unique text written in a form that defies categorization. Subtitled "Improvisations" the closest way to describing the text in familiar genre terms is as a prose poem. Specifically it is a series of paragraph entries comprised of two types of writings: (1) spontaneous writings that he composed over the course of a year -- a kind of poetic diary; and (2) italicized critical commentaries on the "diary" passages. The fragmentary form is an attempt to demonstrate the process of the imagination as it moves "from one thing to another." In doing so Williams is tracing the discovery -- and the movement towards understanding -- that the opposite of a perception can also true. In this way Kora in Hell juxtaposes the tension between -- and interdependence of -- the imagination and the objective facts--the hard objects--of the world.

The "Prologue" to Kora in Hell is considered one of the most significant statements on modern poetic form. At the time Williams was interested in Dada and the ideas of the artist Marcel Duchamp. Kora in Hell was written at the peak of this intense and significant but short-lived avant-garde movement and it is the most fully realized work of Dada poetics. It bears the hallmarks of the movement's in its absurdity, irony, chance, and the need to create art that challenges conventional ideas about art itself. It is profoundly unsentimental and scoffs at exalted conceptions of art:

There is nothing sacred about literature, it is damned from one end to the other.

As befitting a work that evokes the myth of Kora's descent into hell (Kora is a figure for Percephone -- although Williams also connects the theme to Euridice), the work is often deeply pessimistic and despairing about the human condition. It is important to note that the book (and the Dada movement) were created during the time of World War I.

As befitting a work that evokes the myth of Kora's descent into hell (Kora is a figure for Percephone -- although Williams also connects the theme to Euridice), the work is often deeply pessimistic and despairing about the human condition. It is important to note that the book (and the Dada movement) were created during the time of World War I.In keeping with the Percephone myth rebirth is a recurring motif in the work, as is the theme of returning: the flip side of the coin of renewal. This is the necessary journey of the artist who must create a break from the past in order to see the world anew. Indeed, Kora in Hell marks a major transition in Williams as a modern poet.

There is so much more to say about this book but for now let this stand as a brief "advertisement" for you to go read it for yourself.

To cite this passage please contact me here.

Friday, September 08, 2006

sorry about the mess.

Sorry about the current look. I'm working on the new color scheme. If anyone knows how to change the color of the green border areas please let me know. The template code is making me cranky.

kih excerpts

The Center for Book Culture published a few gems from William Carlos Williams' Kora In Hell in their second online edition of Context:

Kora was one of Williams's favorite creations because it revealed "myself to me." We like it because it is incorrigible, uncompromising and very mean to T. S. Eliot and "dear fat Stevens."I don't think he's very mean to Stevens. However, they forgot to mention that he isn't very nice to H.D.! Click here to read the excerpts.

Monday, September 04, 2006

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)